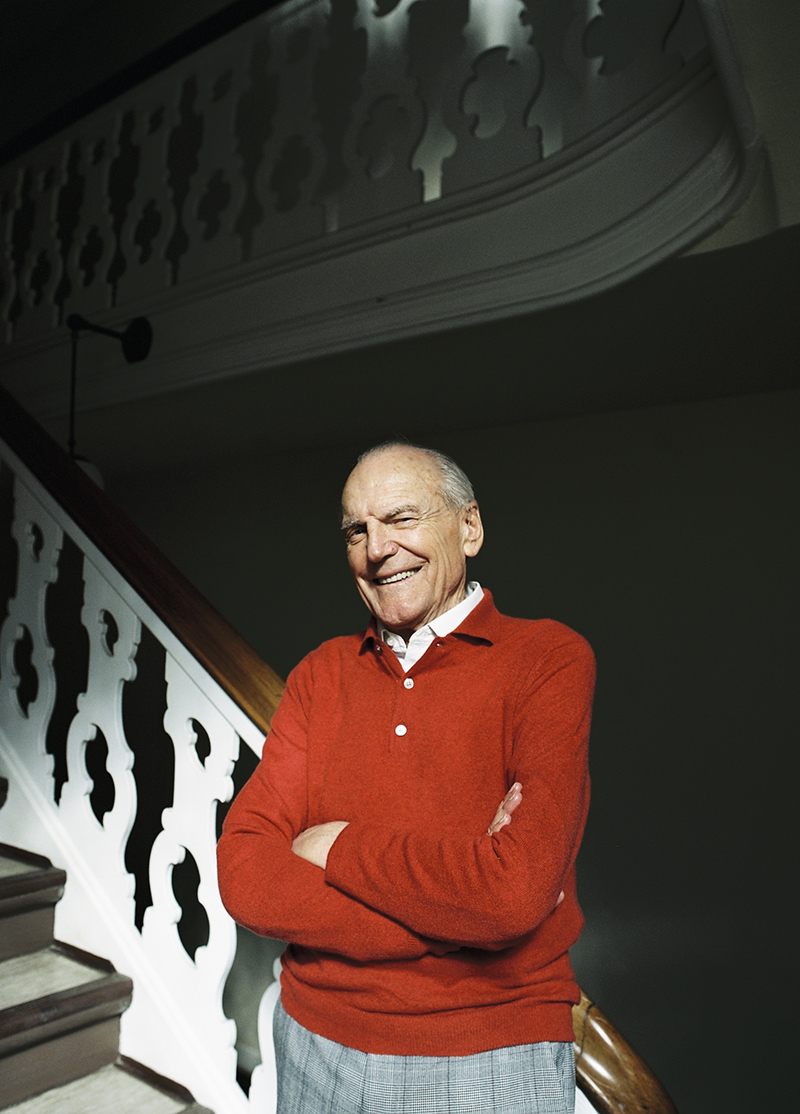

“Yes, in the end it is always personal”: Eugen Baer on Covid and Grief

It turned out to be one of the most memorable summer vacations in my lifetime — I found myself lying on a sunny, picturesque beach in the South of France; being swept away, much like with waves, by the wafting scents of Provençal seaside cuisine; and surrounding myself with three happy children building sea castles in the warm sand. Yet this seemingly Utopian setting, albeit enviable, would serve merely as a backdrop for what became my daily escape into Marcel Proust’s masterpiece entitled, “In Search of Lost Time”. To this day, I cannot minimize the impact that Proust's most notable work, recognized not only for its length but also for its provocative themes, had on my thinking about memory and grief; and I regretted waiting until well into my forties to have placed the tome on my summer reading list.

And since that summer, and after many years of teaching philosophy, I have come to realize that Proustian readers need not slug through all seven volumes in order to grasp the now not-so-hidden gem about involuntary memory, or the Madeleine Effect. Put simply — as the narrator of Proust’s novel dips his French pastry called a "madeleine" into a cup of tea one day, he finds himself suddenly overwhelmed with vivid memories of his childhood. As the story goes, the mere act of tasting or smelling the tea-soaked biscuit, not only triggers a childhood memory of him eating a madeleine with his aunt, it also reveals to him other memories of his childhood home and its surroundings. The narrator relates the incident as being completely involuntary and so vivid that it defied any reality he had ever experienced.

Proust would ultimately be credited with coining the phrase 'involuntary memory' for his Madeleine Effect, and in its simplest form it is identified as an instance when a smell or other sensory mechanism produces an involuntary and highly emotional reliving of events from our past. If only all grieving could be transmuted in a similar way, I mused, as I lay on that French beach.

Grief As We Know It. There is no greater loss in life than the loss of a loved one. And although various psychological stage models of grief have been invented in order to try to understand grief, I often find them too mechanical due to the very subjective, or personal, nature of grief. In basic terms, grieving for me is a subjective state of painful feelings and thoughts manifested when faced with the permanent separation or death of a beloved person or object. The feelings may be conscious or unconscious. They may be expressed communally or personally; but at the core, grief is about the absoluteness of loss in relation to an object of our love.

I would consider my first encounter with grief to be the death of Zesi, my boyhood hound and the only pet I ever had. My deep relationship with Zesi and his untimely death was an experience that would leave its mark on me. And the way in which Zesi died would further traumatize me when I learned that our inhospitable neighbor, who did not like Zesi's barking, fed him a sausage full of poison. I watched helplessly as Zesi stood upright with his whole body shaking before accepting that he was gone forever. My permanent separation from Zesi was an ordeal that I have yet to completely repress; and there have been times in my life when memories of Zesi have resurfaced as a result of my own madeleine moments — the sight of a similar dog, a sound of a bark, the wagging of a tail. If I am completely honest, I would have to admit that perhaps my only source of comfort over the years, albeit most subconscious, has been my refusal to ever replace Zesi by never again owning a pet.

One very peculiar thing about grief is that after a permanent loss, our need to grieve can strike at any moment and be expressed in a variety of ways. Signs of grief can come soon and readily, while for others are delayed or otherwise repressed for a lifetime. For example, Proust revealed that he could not express grief for his grandmother until several months after she died. The pain associated with grief can often occur unexpectedly — it has its own very personal temporality and reality. Also remarkable is that it may express itself by adopting one's own personal views about the universe as a whole.

Grief as an Artform. The pain of grief is often associated with the imagination and can be expressed in many diverse art forms. Perhaps this is why a novelist such as Proust, who was not a psychologist, could so poignantly narrate emotion-driven experiences. In theory, many art forms can help us express grief at the deepest levels of the soul and can also heal some of the rawest emotions caused by grief and loss — music, cinema, dancing, storytelling, sculpture, architecture and many others come to mind. Well-known writers have often emphasized this personal nature of grief. For example, the essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson insisted that he needed to believe in the moral nature of the universe in order to grieve the death of his first wife, Ellen. The death took a huge toll on Emerson who, as a source of comfort, visited her grave daily, writing in his journal: "I visited Ellen's tomb and opened the coffin." (“Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks” of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Volume I., p.7). The novelist John Updike sought comfort in believing in the personal structure of the universe in order to deal with death and dying. "Each day, we wake slightly altered, and the person we were yesterday is dead. So why, one could say, be afraid of death, when death comes all the time?" (John Updike, “Self-Consciousness”).

So why this affinity with art and aesthetics? What accounts for the intimacy between art and grief? Is it not that both are deeply rooted in the unexplainable depth of the imagination? Grief has been the inspiration of the greatest works of art for centuries. In many way, the classic Greek narratives can be read as sagas of grief. In Homer's “Iliad”, for example, Achilles kills Hector out of grief for Patroclus and is killed himself. In Sophocles' play, “Antigone”, the protagonist's grief over her dead brother Polyneices leads to her own demise. One of Picasso’s best known oil paintings, “Guernica”, is one of the most moving expressions of grief over the victims of war.

Since the last century, humankind has been marked by the devastating grief caused by the Jewish Holocaust, and has become a human tragedy forever etched in our collective memories. Having been born in Switzerland, I recall taking in refugee relatives from Germany during the war. Ironically, it was a happy time for me because I found myself surrounded by cousins my own age. It became an opportunity for me to create a lot of memories which helped foster lasting relationships. It wasn't until the war was over that I was able to understand its realities, and which allowed me to personally grieve the horror of it all. And there is especially one story that I can never forget. It is the story of the poet Paul Celan who was born in 1920 to a German-speaking Jewish family in Chernivtsi, Romania (now Ukraine). By the age of 18, Celan was already writing poetry. During the war, however, Celan's mother and father were both murdered by Nazi criminals, while he himself just barely managed to survive.

In the aftermath of the Holocaust, Celan felt he'd lost everything that ever mattered to him, with the exception of one thing: his mother-tongue. So, it was the German language that he chose to express his grief and loss in his poetry. It was for him the only possession that survived the war. In the years to follow, Celan would move to Paris and establish himself as a prominent figure on the literary scene at the time. After receiving the Bremen Literature Prize in 1958, Celan spoke of his language: "Only one thing remained reachable, close and secure amid all losses; language. Yes, language. In spite of everything, it remained secure against loss." And while Celan would never recover from a life grieving the death of his parents, he relied on his German language, albeit a language of exile, as a comfort for his grief. There was nobody who could bring back the dead from the ashes; and there was nobody who could heal that grief. In his poem, "Psalm," Celan writes:

"No one kneads us again out of earth and clay,

No one summons our dust,

No one."

How is it that poets are so able to understand and express the realities of loss, while at the same time inspire us to seek out ways for finding comfort? The great African-American poet and memoirist, Maya Angelou, often mused about grief and loss. In her poem, "When I Think of Death," she confesses to something that many of us have unfortunately learned to be true — that the loss of a loved one is much more painful than the contemplation of our own death:

". . . I can accept the idea of my own demise,

but I am unable to accept the death of anyone else.

I find it impossible to let a friend or relative

go into that country of no return.

Disbelief becomes my close companion,

and anger follows in its wake.

I answer the heroic question 'Death,

where is thy sting?' with 'it is here

in my heart and mind and memories . . .'"

As a way of coping with the loss of a loved one, Angelou first seems to refuse to emotionally accept the reality, perhaps believing that in some way her defiance would bring her loved one back. She admits, however, that her disbelief soon turns to anger, which may serve as a beginning of acceptance. It is only after her anger subsides that her loss turns inward, allowing her to be comforted by her memories.

Covid Grief. Grief, as difficult as it may be, is often accompanied by various types of support systems that tend to help us through the most difficult periods of our lives. Some of these supports systems are traditional or even structural in nature, like estate and inheritance protections; rites associated with funerals, memorials, and burials; public obituaries; life insurance; social security benefits; the reading of the will; death related employment benefits, etc. Fortunately, for many of us these types of entitlements exist during a period of time when we are most distraught; but for many more, they do not.

For the past year, however, we have found ourselves in the midst of a deadly global pandemic, and it is impossible for us to ignore the human suffering due to the impact of illness and tragic deaths. At the time of this writing, over 70 million persons have been infected with the novel COVID-19 virus, resulting in nearly 1.6 million deaths worldwide. As a result, the mere magnitude of death has uniquely complicated how we grieve, not only as individuals and families, but also as a communities, states, and even nations.

After several months of trying to conquer the virus, our personal and shared spaces have been bombarded with stories of grief and loss, with their impact being felt both intimately and empathetically. And as so many of these stories are told and heard, we realize that this pandemic has forced us to deal with great loss without having access to not only the structural supports like those mentioned above, but also the more necessary and basic elements of comfort that most of us rely on to overcome grief; for example — human embraces, a shoulder to cry on, hand-holding, witnessing the progressive signs of death, good-bye rituals, last-word memories, family gatherings, witnessing the grief of others, deathbed conversations, group therapy, etc.

Let's take a moment to empathize with Lesley Branch from Essex, England. Her story appeared in an article in the “New Scientist” entitled, "Grief Over Covid-19 Deaths May Be Unusually Severe and Long-Lasting," by Alice Klein (8 July 2020). Her heart-breaking story details the last moments she shared with her 67-year-old husband:

"He rang me [from hospital] and I got to speak to him for under a minute. We were able to tell each other that we loved each other. I told him he would be OK and I would see him in a few days. His last words were, ‘I hope so and thank you.'

I woke at 4 a.m. to find a voicemail on my phone. It was the nurse looking after him. He died before they could ring me. I was in complete shock. I feel so sad and guilty that I didn’t get to say goodbye or hold his hand.

We were told only 10 people for the service. No clothes to bury him in or anything placed in his coffin. Flowers were hard to get hold of as everywhere local was closed.

The funeral wasn’t attended by anyone other than immediate family and we were seated apart.

Since his death, I find it hard to sleep. No one to comfort me . . . No shoulder to cry on. It’s not a natural way to grieve."

Unfortunately, Lesley's story has become the new normal when it comes to how people are having to deal with their permanent loss(es) during this deadly pandemic. If there is one lesson we continue to learn, it is that in addition to the fear of infection, death and dying, financial distress, job insecurity, hunger and homelessness, etc. — having to deal with COVID-19 continues to put our emotions at risk. Necessary social distancing measures such as limiting our social interactions, wearing face masks, diligently washing our hands, disinfecting our surroundings, and avoiding gatherings (including religious services) come highly recommended, or even mandated. But these same social distancing protections are instrumental in further isolating us and expediently exacerbating our grief.

In spite of all these protocols, health care givers, essential workers, and other front-line laborers are asked to risk their own safety in order to attend to the needs and lives of those greater at risk. With every passing day health professionals, in particular, are in direct danger of losing their own lives and endangering the welfare of their families. And what is worse, these caretakers are left with little time to deal with or express their own grief, left stranded in a sea of last moments and as substitutes for the loved ones of the dying.

Some Signs for Hope. So how do we go on from here? I won't pretend to know how to resolve grief on such a massive scale or even suggest another list of stages for how an individual should recognize or express grief, let alone overcome it. But I would like to offer some hope, if only for the sole purpose of believing that COVID-19 will not have the last word on grief. My hope is that we can learn to develop healing rituals that provide comfort — not only our own personal grief, but also our communal grief, in the aftermath of this pandemic.

I have come to believe that comfort or healing rituals are more effective than stage models, especially since "normal" grieving patterns, as referred to above, are made impossible by the changes brought about by the virus. I like to think of healing rituals as events whose mere symbolism is meant to heal some of the pain caused by the death of a beloved one. The examples above — Celan, Emerson, Updike, and Angelou — shed some light on their own comfort rituals associated with grief.

Often, together with the enormous pain of loss, there is also a profound disorientation of the person hit by grief. It can bring about an existential crisis as it did for the young St. Augustine. In his “Confessions”, he writes that after unexpectedly losing a friend to death, his whole life changed for him. He confesses that not only did his whole world fall apart, but he himself lost a sense of who he was. To counter this, he began relying on healing rituals such as turning inward, reading, religious reflection, and most importantly — searching for a personal God who could save him from the inevitable flow of time. This kind of religion-based comfort ritual is ageless, and I expect that many coronavirus victims have used this framework as they seek relief from the pain and the many questions that remain unanswered.

As always, it's important to note that because grief is personal, healing rituals are endless in their variety. Often, rituals are entirely spontaneous and unconscious as people struggle to begin to cope with new memories and learn to integrate the negative memories without their loved ones around them.

In terms of exploring healing rituals that are more communal in nature; there are signs of hope currently underway. German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, for example, recently suggested that a national memorial service for the dead and bereaved may be warranted — publicly admitting that, "A coronavirus death is a lonely death," after hearing from others just how painful it is to forgo the ritual of bidding farewell to the dying loved ones.

Even prior to the pandemic, many hospitals and health care facilities already had well-developed bereavement support protocols in place. But since the onset of the virus and all the death associated with it, these institutions have tried to enhance their services they offer to those in grief. The bereavement unit at Israel's Sheba Medical Center, the largest hospital in the Middle East, is one example. In response to the pandemic, the Center has constructed an isolated bereavement unit where families can say their final goodbyes to loved ones who have died as a result of COVID-19 by allowing families to safely view the deceased through a large glass windows without risking infection.

"In Judaism and mankind, saying farewell and goodbye [during] mourning is very traditional. In this time of corona . . . most people cannot say goodbye and cannot say farewell the way [they want] . . . [s]ome of them just want to see the process, some of the want to pray, some of them want to say farewell words, [s]o we created the bereavement area in a very protective way while still enabling the families to say farewell and even to see the body." — Yoel Hareven, Chief of Staff at Sheba Medical Center (“Newsweek” 4/17/20).

Since events like funerals and other family traditions are made impossible by the coronavirus, these types of spontaneous rituals can point the way for future healing. Other examples of ritual-like events are being organized by hospitals around the world and in various cultural settings where heroic medical staff and those most deeply affected by the cruelty of the virus find ways to "come together" to share their memories of loss. After all, those most affected by the Corona virus are those who have lost loved ones and those who were charged with taking care of those loved one — doctors, nurses, and other health care providers. Not only does the ritual allow survivors an opportunity to tell their stories and share their grief, but gives caretakers a chance to convey valuable end-of-death details, relay messages, extend condolences, and share insights. While coping with grief and loss is a highly personal experience, much can be learned from how others attend to or express their own emotional and physical needs after permanently being separated from a loved one. For this to happen, the healing rituals offered by the hospitals are a good beginning.

In the past year, I've heard the refrain over and over again — "Remember, we're all in this together!" And when it comes to this global pandemic, this rallying cry can't be more apropos. Think about it, every country around the globe now has a shared experience, with varying degrees of success, when it comes to dealing with grief and loss of all kinds.

At a global or national level we should think about developing even broader communal healing rituals once the pandemic has been virtually tamed and subdued. An appropriate framework could be "what went wrong?, "what can we do better?, how can we protect our most vulnerable populations in the future?, how can we better unite ourselves to fight a common enemy? are we ready for the next pandemic? — so many questions remain.

Such a daunting task reminds me of the rituals the South African Commission on Truth and Reconciliation established over two decades ago for all those who had been victims of apartheid in South Africa, in addition to those who actually committed crimes of injustice. The process was meant to show the power of healing rituals in order to provide a grieving process for a broken society. To be sure, such a ritual could do nothing to change the atrocities of apartheid, but it gave the victims, for the first time, a community which cared for their psychological wounds, giving them a voice for the first time, a forum of recognition, an opportunity to tell their stories. People who had never met each other found a community of agents for change. The ritual also showed for the first time to the world that they, the victims, existed, that they had being, that they were real, and the harm was evident.

Is it possible that a Truth and Reconciliation initiative could serve as a communal blueprint for addressing Corona-based grief and loss? In order to better address the needs of our vulnerable populations in the future, those populations need to be given a forum to express themselves and help provide solutions. Their stories need to be heard and collected by local communities and governments, their isolated suffering needs to be brought to light, they will need to find a community for their grieving, their existence and their suffering needs to be recognized.

Yes, In the End, Grief is Always Personal. Healing rituals can be as simple as writing about it; and poets, as we have been shown, can play a special role when it come to the expression of grief and healing, because words validate the being of each person’s unique personal reality.

In closing, I leave you with yet another fitting Angelou poem, "When Great Trees Fall," which serves as a metaphor for personal grief. Here, I share what may be viewed as Angelou's final stage of grief which purports to be more hopeful, and which fairly represents my own framework for accepting death and dying — namely that the mere existence of the lost loved one in my life is solace enough for me:

". . . And when great souls die,

after a period peace blooms,

slowly and always

irregularly. Spaces fill

with a kind of

soothing electric vibration.

Our senses, restored, never

to be the same, whisper to us.

They existed. They existed.

We can be. Be and be

better. For they existed."

Eugen Baer was Senior Fellow at THE NEW INSTITUTE